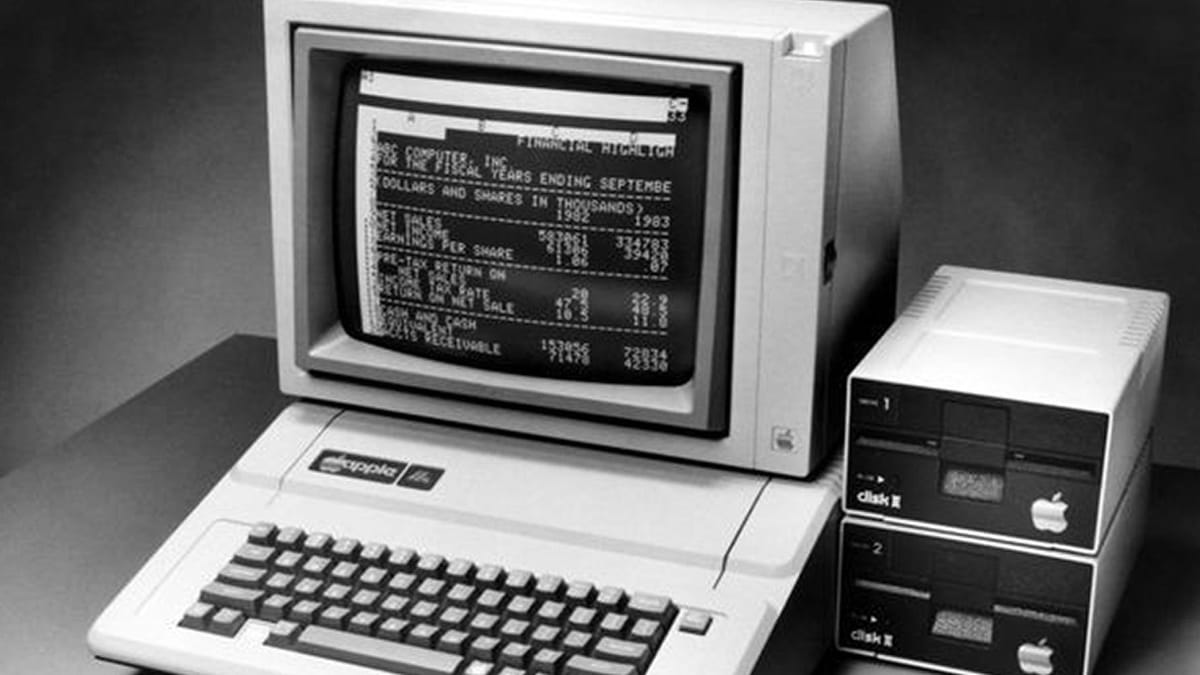

VisiCalc: The first 'killer app'

Before Excel and Google Sheets, there was VisiCalc on the Apple II.

The 8-bit Apple II series of computers established Apple as a giant in the home computer industry. Every great computer needs great software, though, and one application in particular helped push Apple into the mainstream: VisiCalc.

The story of VisiCalc starts with Dan Bricklin, who started programming in Fortran in the mid-1960s while in high school. He received a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering and computer science in 1973, and later worked at the Digital Equipment Corporation as project manager on the WPS-8 word processor, then moved to FasFax Corporation. Bricklin returned to education at Harvard in 1978, where he had an idea for a computer application.

According to Bricklin, he was watching a professor give a lecture with a paper spreadsheet, and the professor found an error in a single cell. He was then forced to change the value in every other cell with the correct calculations. Bricklin believed a pocket calculator outfitted with a small trackball and a simple interface could be used to create dynamic spreadsheets, solving much of the manual work involved in paper spreadsheets. He asked veteran programmer Bob Frankston to help him create the spreadsheet tool.

Dan Fylstra, founder of a software publisher called Personal Software, took interest in the project. Bricklin originally wanted to create VisiCalc for the DEC PDT minicomputer, but Dan convinced Bricklin to write VisiCalc for the Apple II computer, because Steve Jobs had previously sold him an Apple II, and he was impressed by the computer. Personal Software loaned Bricklin an Apple II and paid for the development costs.

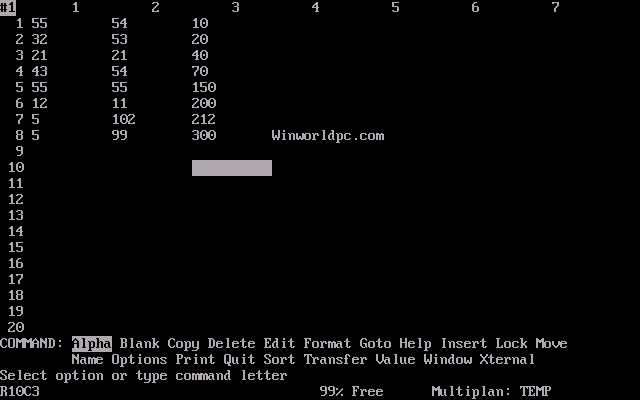

Bricklin quickly created a simple spreadsheet application in the Apple II’s Integer BASIC, which had a set of rows identified with numbers, and columns identified with letters. Each cell could contain data or formulas, and reference other cells using their names — not too far off from modern-day digital spreadsheets. The initial version also allowed users to create nicknames for a given cell for easier reference later. That didn’t make it into the final version of VisiCalc because typos were common, and there wasn’t enough room for long names on the limited resolution of the Apple II and other computers of the era.

Personal Software was impressed with the demo and reached an agreement to distribute the final product. The company offered jobs to Dan Bricklin and Bob Frankston, but they wanted to start a company of their own. The two developers founded Software Arts Inc, which would then act as the developer of VisiCalc. Dan Fylstra (head of Personal Software), Dan Bricklin, and Bob Frankston would each receive 37.5% of revenue as royalties, but sales through computer manufacturers would earn them a 50% share.

The final version of VisiCalc for the Apple II added support for a basic windowed interface, so users could work with two different sections of a spreadsheet at the same time. Bob Frankston also added support for the Apple II’s file system by reverse-engineering it, so they wouldn’t have to pay for a license from Apple. What a legend.

Dan Fylstra discussed some of the early development process in a conference talk in 2004. According to him, the team was worried that VisiCalc was so general purpose that people wouldn’t understand how to utilize it. “Our realization that the general-purpose nature of VisiCalc could be a marketing problem,” Dan said, “motivated us early on to create numerous example worksheets that illustrated what VisiCalc could do. These weren’t random examples – they were aimed at specific markets and applications, including budgeting and financial planning, inventory planning (due to Bricklin), real estate analysis, insurance applications, and the like. We later created a self-running demo for VisiCalc – one of the first tools of its kind – that cycled through a set of these example models. This self-running demo was used in hundreds of computer stores, helping both salespeople and their customers learn what this new tool could do.”

VisiCalc was finally released in November 1979, for the low price of $100 — about $420 (nice) in 2023. When you watch it in action, it’s not too far off from how Excel, Google Sheets, and other similar tools work today.

Early impressions of VisiCalc were positive, especially because it was a significant upgrade from the process of writing BASIC code manually. Ben Rosen for the Electronics Letter wrote, “Though hard to describe in words, VisiCalc comes alive visually. In minutes, people who have never used a computer are writing and using programs. […] We believe that VisiCalc is so powerful, convenient, universal, simple to use, and reasonably priced that it could well become one of the largest-selling personal computer programs ever. It’s hard for us to imagine any professional user of a personal computer not owning – and frequently using – VisiCalc.”

VisiCalc quickly became the killer app for the Apple II, and by most accounts, the first killer app ever. Some reports indicated more than 25% of Apple II computers sold in 1979 were bought specifically for VisiCalc, and retailers started selling VisiCalc and Apple II computers together in bundle packages. Eventually, VisiCalc was ported to the Commodore PET (a predecessor to the VIC-20, which was then replaced by the Commodore 64), Atari 800, and Radio Shack TRS-80.

Meanwhile, Personal Software also hired other developers to create an entire family of products around VisiCalc. There was VisiPlot and VisiTrend for graphics and statistical analysis, the VisiFIle desktop database program, VisiWord word processor, VisiSchedule project management program, and VisiLink and VisiTerm for online database access and terminal emulation. The VisiCalc extended universe grew rapidly, but VisiCalc remained the best seller.

Unfortunately, it didn’t take long for competitors to show up. Microsoft released MultiPlan in 1982, which was a similar spreadsheet program with one critical advantage: it was multi-platform. VisiCalc was written primarily in 6502 assembly code, so porting it to other computers with the same core architecture (like the Atari 800) wasn’t too much work, but bringing VisiCalc to computers like the IBM PC with different processors would require a significant rewrite. Multi-plan was eventually available on the Apple II, Macintosh, MS-DOS PCs, Commodore 64, TRS-80, and other platforms.

Lotus 1-2-3, which was released in 1983 for the IBM PC and other MS-DOS computers, created more competition for VisiCalc. Lotus was founded by Mitchell Kapor, who previously worked on VisiPlot and VisiTrend. Personal Software paid him $1.2 million for the development and full rights to those applications, which in turn was used to start up Lotus. Compared to the IBM PC version of VisiCalc, Lotus 1-2-3 could handle larger spreadsheets with the PC’s 80-column display, since it took full advantage of the extra memory available. It was also compatible with files created by VisiCalc.

There was also internal turmoil at Personal Software — now called ‘VisiCorp’ — over royalties and ownership of VisiCalc, which eventually led to a lawsuit between the two groups. Dan Fylstra’s 2004 recollection includes some specific details about issues with royalty payments from VisiCorp/Personal Software (the publisher) to Software Arts (the developer). Bob Frankston disputed some of that information in a YouTube comment, saying, “there were very serious errors, perhaps libelous errors, in the quotes from Dan Fylstra […] the first turning point was when VisiCorp used a purposely fraudulent spreadsheet to try to change the terms rather than negotiate.”

Regardless of the details, VisiCorp and Software Arts settled their lawsuit out of court in September 1984, which resulted in VisiCorp giving up the rights to VisiCalc and paying out around $500,000 in withheld royalties, but keeping the “Visi” trademark. The damage was already done though. The uncertainty over the application’s future and increased competition caused VisiCalc to plummet in popularity. There were 39,000 copies sold in January 1983, but in December of that same year, less than 5,700 copies were sold.

Finally, Software Arts filed a lawsuit against Lotus in April 1987. Software Arts accused Lotus of copying VisiCalc, specifically its commands, functions, and general appearance. Lotus itself was also suing two other companies at the same time, Paperback Software and Mosaic Software, for creating clones of Lotus 1-2-3. U.S. District Judge Robert E. Keeton dismissed Software Arts’ copyright infringement claims in November 1988, saying the company gave up its right to sue when it sold most of its assets to Lotus in 1985. All other charges against Lotus were dismissed in March 1989, including breach of contract, misappropriation of trade secrets, and confidential secrets and unjust enrichment.

Even though VisiCalc only had a few years in the spotlight, its impact can’t be overstated. The core design and many of the functions from VisiCalc live on in modern spreadsheet applications, and VisiCalc helped establish Apple in the computer industry. Dan Bricklin is still around, serving as the CTO of Alpha Software. Bob Frankston is currently on the Board of Governors for the IEEE Consumer Electronics Society, after working at Lotus in the 1980s and at Microsoft in the 1990s. Dan Fylstra has been President of Frontline Systems since 1988, and at one point was a prominent spokesperson for the Libertarian Party. He published an article in 1998 criticizing the US’s legal action against Microsoft, describing state attorneys general as “Political entrepreneurs who are simply riding the anti-Microsoft wave for all it's worth.” Thank goodness someone was willing to stand up for the poor, innocent, helpless Microsoft.

This article was adapted from an episode of Tech Tales, a podcast exploring the technology world's epic failures, forgotten successes, and everything in between.